Twenty Minutes

by Beth Finke

Guest blogger Keith Hammond is back! Keith is a manager at the adult day services program at Easterseals Serving Greater Cincinnati, and he’s the father of two children on the autism spectrum. He’s written a number of poignant posts for us before, and I’m delighted to have him back with another one.

by Keith Hammond

Keith with his daughter and son

Recently, my wife and I took our son, Steven, to meet with a speech therapist he last saw in 2014. We reconnected with her on Facebook, and found out she was open for some sessions.

Steven has autism. He is non-verbal and communicates by RPM or Rapid Prompting Method — a board with the alphabet on it prompts him to respond and spell words to communicate. RPM is a relatively new technique; few people are adept at it.

Even with this tool, though, Steven has to feel some sort of a connection with people before he’ll communicate with them. Often, and with no pattern we can find, he chooses not to communicate at all. Even as his family, complete thoughts and sentences are something we rarely get. We usually only get simple “yes” or “no” responses, and we consider them as beautiful gifts.

As such, we re-engaged this speech therapist. At the first session, Steven and the therapist picked right back up communicating as if the absence had been four minutes instead of four years. It was great to watch — something we rarely experience.

After about forty minutes of the two of them discussing a history lesson, the therapist stopped and said, “We have twenty minutes left in the session; is there anything you all want to ask him?”

That really hit me. Twenty minutes. Think about that for a second. If you and your 17-year-old son had almost no communication, and then all of a sudden you were given twenty minutes to communicate… what would you say?

It’s a question most people never have to deal with. It’s a question so powerful, my mind darted about, jumping from one thought to the next in a song-like trance. After 17 years, there could never be enough time to ask him everything I want to know. Instead, and for reasons I cannot explain, a sampling of the questions took shape in a humble poem:

Would you like to have more friends?

Why are you so scared of the cat?

Do you like your summer camp and therapy?

Or could you do with less of that?Are there shows you want to see on TV?

Are there certain songs you’d like to hear?

What’s your greatest, secret passion?

What’s your deepest and darkest fear?Are there cities and states you’d like to visit?

Are there special sites you’d be excited to see?

Do you even know what autism is?

Would you like to ask God “Why Me?”Are there actions we can do to support you?

Can we remove barriers that cause you strife?

What else can we do to make things better?

How can we help you have a happy life?Would you like a girlfriend of your own?

Someday, would you like a kid or two?

What do you want to do after high school?

Is there a job or career you really want to do?What do you want the future to hold for you?

Where do you want to live in a few years?

What’s so funny when you’re laughing?

Is there some reason when we see your tears?Would you like new experiences to keep you busy?

Do we help you get enough rest?

Do you know how we feel when we fail you?

Can you understand that we try our best?Are you truly happy with your life?

Or do you feel like it’s all so unfair?

Do you know how much we love you?

Can you feel how much we care?There’s so many things we would love to ask you.

I honestly don’t know where to start.

Most parents have forever; we get 20 minutes.

It’s enough to break the strongest heart.

Ultimately, though, even if Steven is unable to provide the answers, I believe that someday we’ll all be together in heaven, and we can ask Steven our questions there.

One nice thing about eternity: it’s a lot longer than twenty minutes.

I don’t know what the weather is like where you are, but here in Chicago April has been cold, cold, cold — it snowed on the Cubs opening game day! I’m blaming the weather for it taking so long for me to acknowledge here on the Easterseals blog that April is Autism Acceptance Month.

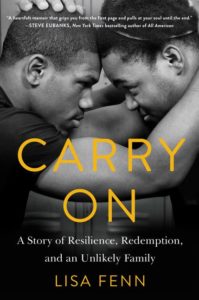

I don’t know what the weather is like where you are, but here in Chicago April has been cold, cold, cold — it snowed on the Cubs opening game day! I’m blaming the weather for it taking so long for me to acknowledge here on the Easterseals blog that April is Autism Acceptance Month. This story is deeply personal. While it is interwoven with strong and sharp threads of Leroy’s and Dartanyon’s stories — and those of other key figures — this is Lisa’s story. From early childhood memories to blustering and fumbling her way to a dream job to high school wrestling matches and beyond, We get to know Lisa as a warm-hearted woman who yearns for a family. And she definitely gets her wish! We’re introduced to athletes, to coaches, to parents and siblings. We laugh, we cry, and we hope and despair. But, make no mistake, this is Lisa’s story.

This story is deeply personal. While it is interwoven with strong and sharp threads of Leroy’s and Dartanyon’s stories — and those of other key figures — this is Lisa’s story. From early childhood memories to blustering and fumbling her way to a dream job to high school wrestling matches and beyond, We get to know Lisa as a warm-hearted woman who yearns for a family. And she definitely gets her wish! We’re introduced to athletes, to coaches, to parents and siblings. We laugh, we cry, and we hope and despair. But, make no mistake, this is Lisa’s story.

On the day of my job interview, I turned from nervous to excited. At least, while I was on the bus.

On the day of my job interview, I turned from nervous to excited. At least, while I was on the bus. Once I settled in after transferring colleges, I decided it was time to apply for a job.

Once I settled in after transferring colleges, I decided it was time to apply for a job.