How Easterseals Helped Support My Family

by Blog Writers

By Dom Evans

I’m not sure of the first time I remember hearing about Easterseals, but I know I was young. I was a child, who had recently been diagnosed with a neuromuscular disability.

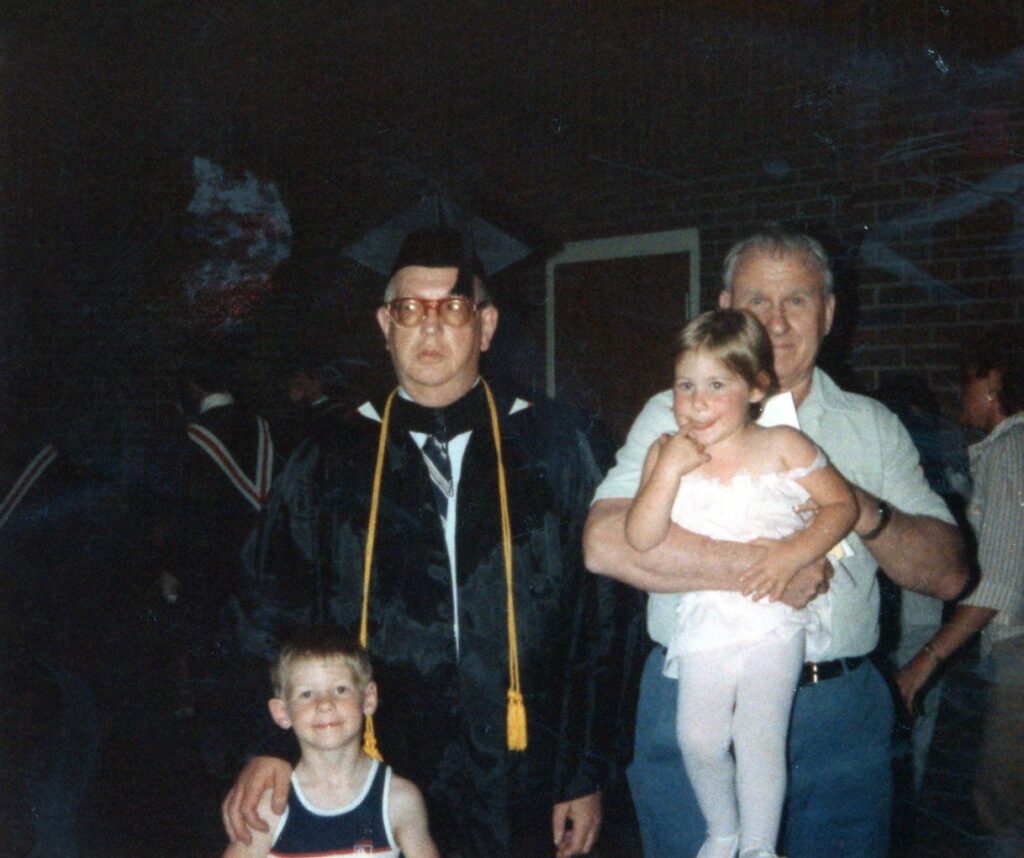

It may have actually been before my diagnosis was confirmed. My father had recently been laid off from his job as a tool and die maker. He and my mother were both in school, as he had returned to a community college to get a degree in accounting, hoping for a better job.

It was a very tough time for my family, monetarily speaking. I needed things like orthopedic shoes, leg braces, and various other equipment to help with physical therapy and other things that kept me mobile.

My father, meanwhile, was deaf. Even today, most insurances won’t pay for hearing aids and, without hearing aids, my father was completely unable to hear.

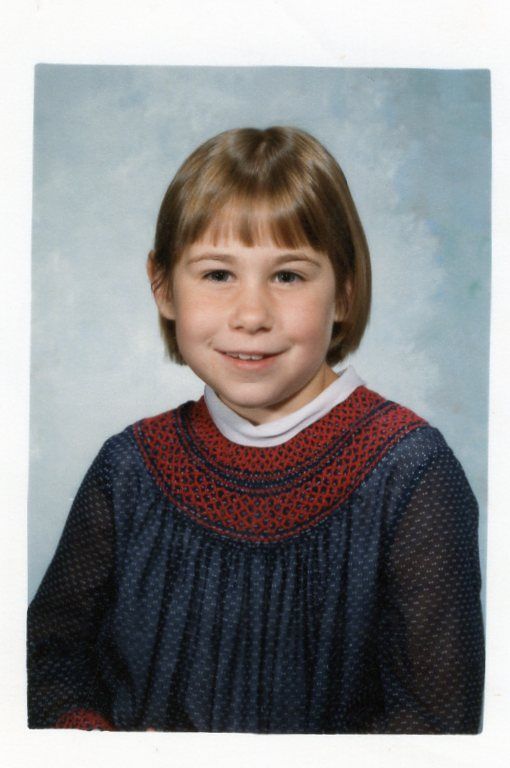

Dom and their father

I don’t exactly know my father’s story, but I think he became deaf in his teenage years or early adulthood. He didn’t really talk about it, and I feel like it was somewhat shameful for him. I do know he was not born deaf, or he could at least hear some when he was a child.

As such, he had no connection with the Deaf community. He could hear a bit (though not well) with hearing aids, but otherwise he would be unable to hear or communicate with anyone. Taking out his hearing aids meant the communication was always one-sided as we could not communicate with him very well or easily.

I know that he got his hearing aids paid for by Easterseals, allowing him to continue to go to school and eventually work. I wish my father was able to learn ASL and also develop a sense of pride in who he was, but unfortunately, he was born in the 1930s, and it was seen as a deficit when he lost his hearing.

I was told when I was young that his hearing loss had a genetic component to it and that I had inherited it, but on a smaller scale. I’ve always struggled with hearing and used to fail all my hearing tests. Even today, people constantly have to repeat themselves and I struggle to hear things, especially when people whisper or speak quietly.

While I never needed hearing aids or anything like that, all of the testing that both my father and I received were paid for by Easterseals. Because of my hearing loss, I had to go for regular hearing testing to make sure my hearing was not getting worse.

I was involved with more than one disability-related organization, and I have to say that Easterseals was a much better experience than the other organizations.

I didn’t have to do any tricks, perform any services or do anything special to get help for what I needed health care-wise from Easterseals. The other organizations wanted more of me. Easterseals just cared that I had a need that needed to be filled and they gave me the resources that my family needed so that we were accommodated and had the equipment we needed.

Just by being serviced by Easterseals, both my father and I were invited to the Easterseals holiday parties for the years when I was getting Easterseals services. They would give us presents, something that I was always grateful for because my family was not rich – so being a kid, I loved that.

I’m certain I went to a few of their parties and it didn’t feel like pandering or like the organization felt sorry for me or my family. It felt like an organization that genuinely wanted to help.

I’m certain I went to a few of their parties and it didn’t feel like pandering or like the organization felt sorry for me or my family. It felt like an organization that genuinely wanted to help.

When I was getting services from Easterseals in the late 80s/early 90s, it was a very confusing time for me. I had been through a lot of medical tests as they had tried to determine what my disability was. It wasn’t until I was five years old that they really figured it out. My family was really really struggling financially, and Easterseals helped lift the medical burden from my family.

I only stopped getting services from Easterseals after my father got a job with the state as a tax commissioner agent, auditing large companies like Campbell Soup. His state insurance paid for my medical needs.

After I stopped receiving services, my father still got support from Easterseals with all of his needs surrounding his hearing loss. I know for a fact that he would not have been able to get his hearing aids without Easterseals, and that would’ve created barriers that he would not have been able to overcome to be able to work and live independently. That’s the kind of thing that Easterseals gave to him.

My father did not have an understanding about disability pride or even that he could consider himself disabled. There was always a level of uneasiness surrounding his deafness. I believe he also experienced a lot of internalized ableism/audism, but because of the way Easterseals was willing to help us – no strings attached, no promoting us in negative ways, and not owing them any favors – I believe he was better able to accept their help and was very grateful for it.

Easterseals has always been about helping disabled people. They help by providing accommodations. They help by removing the financial burden that many of us disabled people face. They offer families hope and support. There are a lot of organizations that claim to help disabled people in this way, but they are not doing nearly what Easterseals has been doing for over 100 years.

As I’ve gotten older, I’ve been proud to see that Easterseals continues to want to help move the needle forward when it comes to access and inclusion for disabled people. While a lot of nonprofits say they want to help us, few of them are actually doing so. I’m thankful for all that Easterseals has done for me and my family, and I’m grateful that they keep wanting to help push the needle forward and make the world a little better for all of us.

Dom Evans is the founder of FilmDis, a media monitoring organization that studies and reports on disability representation in the media. He is a Hollywood consultant, television aficionado, and future showrunner. His knowledge and interest on disability extends through media, entertainment, healthcare, gaming and nerdy topics, marriage equality, sex and sexuality, parenting, education, and more.

Doug Finke, a trombonist of 23, was drafted in 1965 and remained in service until 1967. He knew from the beginning that he wanted to play music while in the service, and chose to pursue the Marine Corps’ music program. When he finally had the chance to try out following boot camp, he was promptly given a trombone to use and music to play. At the end of the difficult audition, they said, “okay, you’re in.”

Doug Finke, a trombonist of 23, was drafted in 1965 and remained in service until 1967. He knew from the beginning that he wanted to play music while in the service, and chose to pursue the Marine Corps’ music program. When he finally had the chance to try out following boot camp, he was promptly given a trombone to use and music to play. At the end of the difficult audition, they said, “okay, you’re in.”

“At 7 or 7:30 in the morning, we would march in uniform from the barracks to the main flagpole on the base to raise the colors. We would play while marching down the streets, and when we arrived at headquarters, we would play a bugle call to attention and “The Star-Spangled Banner”; and then we would march back, playing marches again.

“At 7 or 7:30 in the morning, we would march in uniform from the barracks to the main flagpole on the base to raise the colors. We would play while marching down the streets, and when we arrived at headquarters, we would play a bugle call to attention and “The Star-Spangled Banner”; and then we would march back, playing marches again.

Members of the military are part of a community, depending upon one another to achieve their collective mission. When leaving service, the loss of community can be one of the biggest adjustments that the veteran must make, so finding support from a new community can be immensely helpful. Easterseals recognizes the value of those connections and can help introduce military families to others who share their experiences.

Members of the military are part of a community, depending upon one another to achieve their collective mission. When leaving service, the loss of community can be one of the biggest adjustments that the veteran must make, so finding support from a new community can be immensely helpful. Easterseals recognizes the value of those connections and can help introduce military families to others who share their experiences.