The IEP is the Foundation of a Disabled Student’s Education – This is Why They Are Necessary

by Blog Writers

by Dom Evans

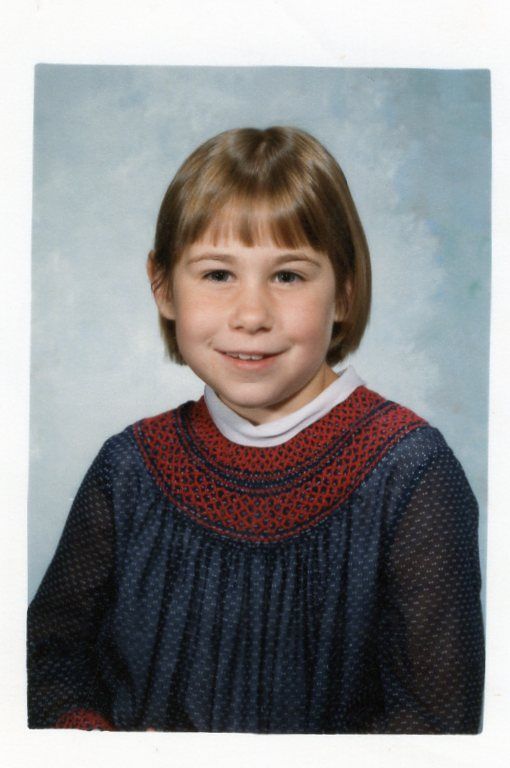

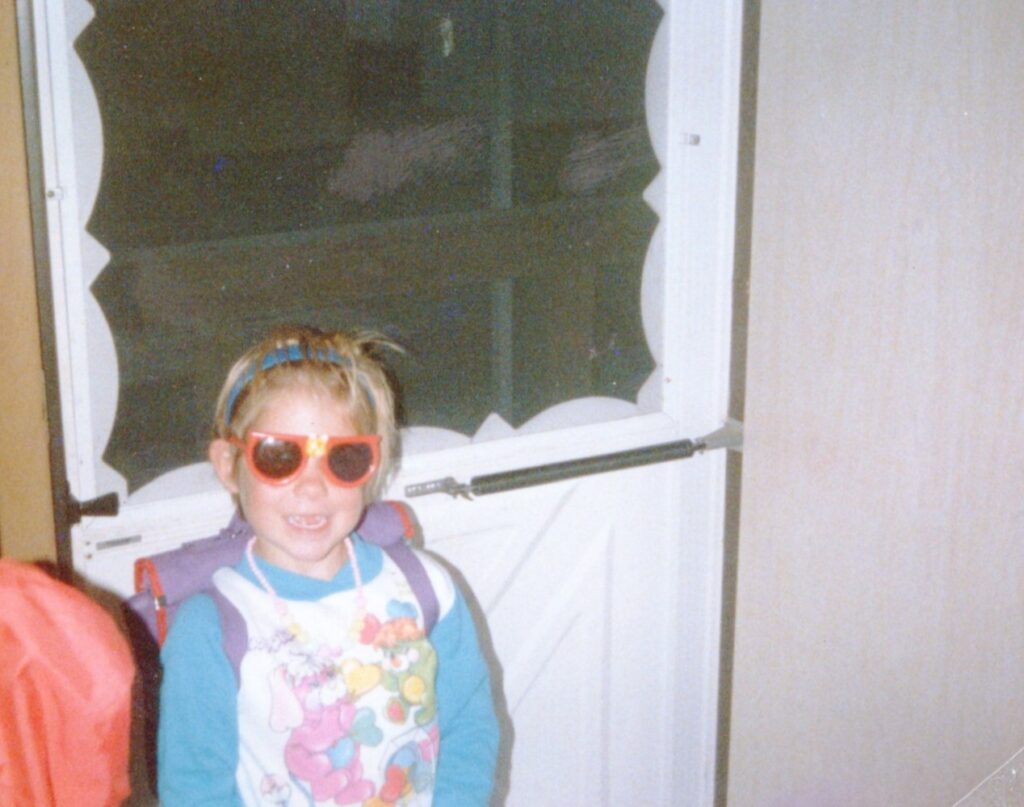

The first time I realized I was different because I’m disabled was in kindergarten. It was 1986. I was five and a half, and the school I was attending didn’t want me to attend. The previous year, they had given me testing. I still remember being a teenager and discovering the test results in a drawer stating that my grade level was above first grade for everything but math (first-grade level for math), but because of my disability, they didn’t want to enroll me.

“She is intelligent, but shy to answer questions. We fear she will be unable to handle the emotional toll of her deficits at school.”

I had an older brother who used to get extra worksheets from his teachers. During the summer, we would play school, and at four, I could add, subtract, multiply, and divide. I could also spell simple words. That didn’t matter to this small farm school in Northwest Ohio. I was “defective” to them, and they would try to prevent me from attending.

In finding this paperwork, I also learned that I had multiple IEPs. Unfortunately, I also discovered I didn’t have one every year. Did my mother not know that they were required yearly? Or did she just not care? I found IEPs for kindergarten, second, sixth, seventh, and ninth grades. This explained why I did not have accommodations.

I desperately needed my own aide who could help me with getting my coat on and off, getting my books, and generally being prepared for class. That did not happen. Instead, junior and senior year I shared my best friend’s aide since he also was a wheelchair user. His mother also must’ve been better at advocating for him since his needs were met. If he did not come to school though, I had no help or had to find a peer or teacher.

That was the school solution — have a peer do it for free. The problem is, I was not well-liked. I was picked on and tortured extensively. I’m even in a book about hate crimes outlining an incident that happened at my high school when I was in 10th grade. That’s how bad the bullying got. I was not exactly comfortable asking for help as a result of this. I did have two girls I trusted — one would sometimes help me get my coat on and off, so I didn’t have to wear my coat all day every day at school. Another would help me get my lunch tray. Other than that, though, I was on my own.

Unfortunately, I didn’t understand my own rights. I spent many days ill prepared for class because I never had the books I needed (could not reach my book bag or my locker). This meant my teachers often yelled at me and complained about me because I never had my books ready and often needed to interrupt class to get help. I also spent many days in my coat because I was too stubborn, afraid, or annoyed to ask someone to help me take it off.

When the peer who helped me with lunch was not in class, I sometimes didn’t eat. I would also skip class and sometimes sit in the elevator or in the accessible bathroom stall just so I didn’t have to go to class. Nobody ever noticed I was missing or said anything. It often felt like nobody cared if I was there or not, so if they didn’t care, why should I?

Luckily, I didn’t let this affect my grades, but I know many students who this would’ve happened to as well. I knew that I needed to get out of my current living situation and going off to college was the best way. That’s the thing that kept me motivated to keep working, but I have so many disabled friends I know that never tried because what was the point?

Luckily, I didn’t let this affect my grades, but I know many students who this would’ve happened to as well. I knew that I needed to get out of my current living situation and going off to college was the best way. That’s the thing that kept me motivated to keep working, but I have so many disabled friends I know that never tried because what was the point?

Having access to the bathroom was also a nightmare. Up until junior high, I could go myself, although there was a horrible bullying incident in second grade where a girl body slammed me with a door, and I flew across the bathroom and smashed into the metal trash can getting injured in the process. In junior high, I was forced to have my junior high classes at the high school (the two buildings were connected by a bridge) since the junior high building was not accessible.

The high school bathroom had accessible stalls, but I couldn’t use them. I would go from 6 a.m. until 3 p.m. without going. When I was in ninth grade, one of my teachers started helping me use the toilet so I didn’t have to hold it. It was a private situation the school didn’t even know about. This teacher went above and beyond to help. I am very grateful to her, but she was risking her job to help me.

Because I didn’t have regular IEPs, the school was ill-prepared to handle situations that affected my needs. In elementary school, there were battles over forcing me to run in gym, go ice skating, or participate in basketball — none of which I could do physically. In every case, it was always presented as my fault that I could not do these things. But by junior high and high school, I was no longer required to take gym at all thanks to a doctor’s note.

This also meant they could get away with kicking me off the school bus in fifth grade. The bus driver would grab my hand and pull me onto the bus, but that year he told me I was “too fat” and I was kicked off. My mother ended up having to take me to school at 6 a.m. before she went to work, and I would sit in a dark classroom and wait for my peers and teacher to arrive. By junior high, I was finally allowed to ride the short bus.

All the failures I saw at school were because my disabilities were not accommodated. This also set me up for a lack of understanding about how to accommodate myself in college where I had to advocate for myself. It’s been a huge learning curve about understanding how to access services, get what I need, and feel like I deserve accommodations. I believe the way my educational career started had a huge impact on all of this.

When considering schooling for yourself or your child, you must start with the IEP. Not having one led to many difficulties, and it also allowed the school, my teachers, and my peers to treat me in ways that no disabled person should ever be treated. Schools must understand that we are entitled to education. We are entitled to learn. We are entitled to accommodations and it’s their job to provide it. Setting a foundation for school that begins with discussions about how participation can occur is foundational to all of this.

Start with a good foundation at school and work from there — that’s the key. I didn’t have one and I’m still struggling to get over the effects of my poor education at 42. I hope for better for the next generation.

Dom Evans is the founder of FilmDis, a media monitoring organization that studies and reports on disability representation in the media. He is a Hollywood consultant, television aficionado, and future showrunner. His knowledge and interest on disability extends through media, entertainment, healthcare, gaming and nerdy topics, marriage equality, sex and sexuality, parenting, education, and more.