by Beth Finke

Guess who spent Saturday afternoon playing the very same piano architect Frank Lloyd Wright practiced on 100+ years ago?

Guess who spent Saturday afternoon playing the very same piano architect Frank Lloyd Wright practiced on 100+ years ago?

Me!

The Frank Lloyd Wright Trust is one of 31 cultural organizations that are partners in Chicago’s ADA 25 for 25 Cultural Access Project, and to celebrate the 25th anniversary of the Americans with Disabilities Act, the trust is offering special ASL and touch-tours of its historic sites.

The goal of the 25 for 25 Project is to help at least 25 cultural organizations in Chicago commit to improving accessibility for visitors with disabilities in 2015 in some concrete way, and then putting plans in place to continue to take steps to improve accessibility after this anniversary year.

Last Saturday my friend Linda Downing Miller, who lives in Oak Park, Illinois, accompanied me on a special tour of Frank Lloyd Wright’s home and studio there. Linda earned an M.F.A. from Queens University of Charlotte — her fiction is forthcoming in Fiction International and appears in the current issue of Crab Orchard Review. She’s a fine writer, and I was delighted when she offered to write this guest post describing our tour from her point of, ahem, view.

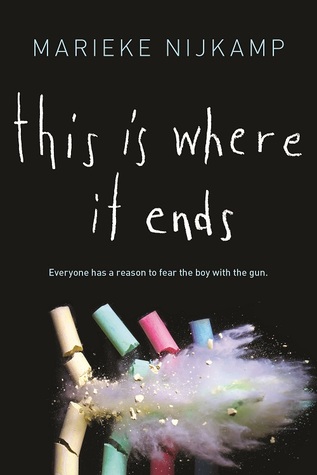

Beth playing Frank Lloyd Wright’s piano

Touching moments in architecture

by Linda Downing Miller

Twenty years ago, I was infatuated with the architect Frank Lloyd Wright. Moving to Oak Park, Illinois, can do that to you.

The village has a wealth of Wright-designed spaces, and I toured as many as I could in my first years here. My husband and I must have taken every visitor we had through Wright’s home and studio, restored to its appearance when he last lived there in 1909.

When Beth invited me to go with her on a Touch Tour of the home and studio last Saturday, I said yes mostly for the chance to spend time with her. I figured I’d already seen and heard enough about Wright’s work: his horizontal lines and ribbon windows and half-hidden entrances, reached by walking a “path of discovery” that usually includes a turn or two.

The Touch Tour took me on a new path. I was one of a handful of people accompanying friends or family members who are blind or have low vision. The Frank Lloyd Wright Trust offered the tour in honor of the 25th anniversary of the Americans with Disabilities Act, part of ADA 25 Chicago — a larger project to improve the quality of life for people with disabilities. Being Beth’s companion on the tour, alongside her Seeing Eye dog, Whitney, allowed me to “re-see” Wright’s spaces and consider the challenge of making them accessible through other senses.

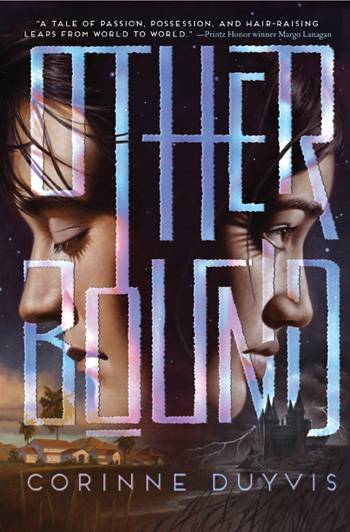

Beth feeling some sculptured parts of the exterior of the building

Fellow writers might appreciate this observation: details, creative comparisons, and specific word choices helped to convey Wright’s work. Our tour guide, Laura Dodd, explained the position of design elements in relation to bodies (“about neck high”). She used similes (wood beams arranged “like an asterisk”). I told Beth that Wright’s intricate, wood-carved designs on the dining room and playroom ceilings were a bit like the wooden trivets she’d felt in the gift shop. A tour volunteer described the vaulted ceiling in the children’s playroom “like a whiskey barrel.”

After thinking about Laura’s description of the way the Wrights’ piano sat in that room with only the keyboard showing, the back half hidden behind the wall, one of the visitors who couldn’t see articulated it more clearly for all of us: “You mean, it’s embedded in the wall.” Yes.

Enthusiasm, curiosity, puzzlement and understanding moved across people’s faces as they listened and asked questions, and as they touched things: fireplace tiles, wall coverings, sculptures, spindles, glass windows and Wright’s famously uncomfortable straight-backed dining chairs. Some people lingered over each touch opportunity. Others eagerly applied their fingers and moved on. (Guess which style was Beth’s?)

She and I talked afterward about the different frames of reference people might have brought to the experience. Beth knew something about architecture before she lost her sight. Other visitors may have been born blind. Laura is the Director of Operations and Guest Experience for the Frank Lloyd Wright Trust, and she asked us for feedback during and after the tour. (The Trust plans additional Touch Tours, and American Sign Language Tours, at its historic sites.)

Our group’s consensus was that she’d done a wonderful job. I thought the three guide dogs in the group also handled themselves well in close proximity.

One of the highlights for me and Beth was when Laura invited her to sit at the piano in the children’s playroom. After instructing everyone else not to pay attention, Beth put her fingers on the keys and ran through a short, jazzy tune. When she’d finished, she and I exclaimed over the fact that Frank himself no doubt played those keys. I felt the ghost of my old infatuation. On our way downstairs, Beth reached up to touch the back end of the piano, suspended over our heads, and continued on her path of discovery.

Photos courtesy of Christena Gunther, Founder & Co-Chair of the Chicago Cultural Accessibility Consortium.