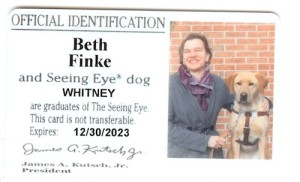

by Beth Finke

Art teacher Jessica Jones working with one of her students.

Lavelle School for the Blind in New York contacted us this past summer about their gardening program for kids with visual impairments. Horticulture therapy programs for students who are blind or have other disabilities are popping up all over the country, and while Lavelle’s gardening program is terrific, I’ve heard of gardening programs like theirs before. What I’d never heard of is someone teaching art to blind students…who is blind herself.

Jessica Jones lost her sight at age 37 due to complications of Type 1 diabetes. Before then she’d been employed by New York City’s Department of Education teaching art in the schools, and she was determined to continue that career after she lost her vision.

“It never even occurred to me that I wouldn’t be able to go back into the public school classroom and teach art,” Jessica told me during a phone interview. “But when I actually was out there interviewing I was shocked at how difficult it was; I was utterly shocked. But did I ever think I couldn’t do it? No.”

Difficult as it was, Jessica persevered and eventually landed her job at Lavelle, a public-private school in The Bronx. These notes from our phone interview help explain how she teaches art to the 100+ students with blindness and other disabilities who are enrolled there:

Jessica: I do just about everything that you can imagine. I’ll start at the top of the list and when you get tired just tell me. We do a lot of painting, I will always have some sort of tactile element involved if the child requires it, or if they want to go back and feel what they’ve done. There are always the obvious things like sand or lentils, and there’s also Ms. Jessica’s Magic Paint, which is plain old tempera paint that has school glue and shaving cream added to it. So it gives you a really raised surface to feel.

One of Jones’s students

Beth: What other tactile stuff do you do? Mosaics, sculptures, clay?

Jessica: We do a lot of print making. Cardboard is an art teacher’s best friend, and the kids make their own printing plates out of cardboard. I’ll give them a two-foot square of cardboard and then if they have the ability to cut out their own shapes they do so and glue those down where they’re composing their image. If they’re not able to, I give them pre-cut shapes and they’ll glue those down where they want. And then, just like print makers do with linoleum, you apply the ink that has been mixed with sand to the surface of this cardboard printing plate with a brayer, put your paper on top and you rub, rub, rub. Pull it off and you have a captive print.

Beth: Sounds like fun! Is printmaking one of their favorites?

Jessica: I honestly have to say, the primary love among my kids is sculpture. I have a lot of kids who have really taken to sculpture both figurative and abstract. They use things out of the recycle bins. I’m always pushing kids to recycle because I believe in recycling. I tell the other teachers all that stuff you’d send to the Salvation Army, put it in the art room. I’ll find a way to use it!

Beth: What thing do you like best about your job?

Jessica: Oh gosh, what is the best part? I think the best part is probably seeing the light go on. You know, I’ve been teaching at the same school now for 11 years. There are some kids that I’ve been with since they were three and a half years old, and it may take them that long to get something as simple as folding a piece of paper, but once they do it, and they do it all by themselves, they’re just so absolutely pleased with themselves. “I get it… now I get what she’s been trying to get me to learn for so many years, and I hated her for trying to get me to learn it, but now I get it”. That’s what I love, is seeing their lightbulb go on over their heads.

Beth: Can you share a specific example of a lightbulb moment?

Art created by Jones’s students.

Jessica: I’ll give you an example where it happened for all of my students at once. We put on our second annual Lavelle school art show in April of this year and people came from all over to see it. Friends of mine that work in museums, people from the community, people from the State Commission for the Blind, people from the Department of Education, newscasters and newspapers. The first year the kids were absolutely thrilled to get all that recognition, but this year I noticed something different. They stepped up the work they were doing for this year’s exhibit.

They recognized they were bringing their abilities to the community at large, not just mom and dad. Not that mom and dad are not important because goodness knows, they are. But the children, this year they stepped up the work they were doing to be a part of the community at large — which a lot of time they are not. It wasn’t just about the attention anymore, it was more about being an artist. “I’m not just a student, I’m an artist, and I have something to contribute to the community at large, that you might not think I have the ability to contribute.”

Easterseals offers art therapy programs for children and adults with disabilities at select locations across the United States. Find your local Easterseals for more information.

For the fourth year in a row, the consumer finance website WalletHub has named the Kansas City, Missouri, suburb of Overland Park #1 in a ranking of the best American cities for people with disabilities. San Bernadino, California came in at last place, #150.

For the fourth year in a row, the consumer finance website WalletHub has named the Kansas City, Missouri, suburb of Overland Park #1 in a ranking of the best American cities for people with disabilities. San Bernadino, California came in at last place, #150.

A teacher once asked me, “Do you need any help?”

A teacher once asked me, “Do you need any help?” Aaron Likens, author of Finding Kansas: Decoding the enigma of Asperger’s Syndrome, and the National Autism Ambassador for Easterseals, has spoken to over 80,000 people at over 900 presentations and has given to the world a revelation of how the Autism Spectrum Disorder mind works. His willingness to expose his inner most thoughts and feelings has unveiled the mystery the Asperger’s mind. Join him on his journey from hopelessness to hope.

Aaron Likens, author of Finding Kansas: Decoding the enigma of Asperger’s Syndrome, and the National Autism Ambassador for Easterseals, has spoken to over 80,000 people at over 900 presentations and has given to the world a revelation of how the Autism Spectrum Disorder mind works. His willingness to expose his inner most thoughts and feelings has unveiled the mystery the Asperger’s mind. Join him on his journey from hopelessness to hope.

One of our focuses here at Easterseals is ensuring children of all abilities have the best possible start in life. Through our

One of our focuses here at Easterseals is ensuring children of all abilities have the best possible start in life. Through our

In my life there has been one constant that’s been worse than any other event: When someone says, “But Aaron, it’s not that difficult!” When those words are uttered I’m devastated.

In my life there has been one constant that’s been worse than any other event: When someone says, “But Aaron, it’s not that difficult!” When those words are uttered I’m devastated. Employment and having a disability (I have Asperger’s syndrome) can be a tricky combination. It can be even more difficult to navigate when one doesn’t know they are on the autism spectrum. I navigated my first several jobs not knowing (I was diagnosed at age 20).

Employment and having a disability (I have Asperger’s syndrome) can be a tricky combination. It can be even more difficult to navigate when one doesn’t know they are on the autism spectrum. I navigated my first several jobs not knowing (I was diagnosed at age 20).

Today’s blog is going to use the most traditional of all things in Motorsport, the checkered flag, as a concept to describe Asperger’s.

Today’s blog is going to use the most traditional of all things in Motorsport, the checkered flag, as a concept to describe Asperger’s. The Senate Finance Committee is meeting this Monday, September 25 for a hearing on the

The Senate Finance Committee is meeting this Monday, September 25 for a hearing on the