When I Finally Called Myself Disabled

by Erin Hawley

By Erin Hawley

It wasn’t until my early college years that I referred to myself as disabled. Growing up, I was one of the only visibly disabled kids at my school, and all my friends were either not disabled or not out about their disabilities. Since I’ve had Muscular Dystrophy my whole life, my own disability was nothing odd to me or a hardship I had to endure; sure, days or even months were difficult at times because of ableism or my own health – but who doesn’t have bad days, and aren’t some people just extremely ignorant? In my mind, I was a nondisabled person with nondisabled friends.

I was not in denial. I knew I had Muscular Dystrophy. I knew I was physically different from other people in my small community. But growing up with telethons and being bombarded with depictions of disability that centered pity and wanting to be “normal” was not something I related to at all. To me, disability was pity – and I liked who I was too much to apply that label to myself. I didn’t want to change and knew I didn’t have to. I am forever grateful that my parents instilled in me that I could do and be whatever the heck I wanted, and continually fought for my rights and acceptance when I was too young or unaware to fight on my own. My mom was a beast when it came to sticking up for me – something I didn’t fully realize until I had to stick up for myself. I’ve learned much from my parents about advocacy simply by being their disabled daughter in a society that wants to sequester me from my community – and their refusal to let that happen.

I was not in denial. I knew I had Muscular Dystrophy. I knew I was physically different from other people in my small community. But growing up with telethons and being bombarded with depictions of disability that centered pity and wanting to be “normal” was not something I related to at all. To me, disability was pity – and I liked who I was too much to apply that label to myself. I didn’t want to change and knew I didn’t have to. I am forever grateful that my parents instilled in me that I could do and be whatever the heck I wanted, and continually fought for my rights and acceptance when I was too young or unaware to fight on my own. My mom was a beast when it came to sticking up for me – something I didn’t fully realize until I had to stick up for myself. I’ve learned much from my parents about advocacy simply by being their disabled daughter in a society that wants to sequester me from my community – and their refusal to let that happen.

When I was in high school in the 90s, social media as we know it today was not a thing. We had dial-up internet, AOL, message boards, instant messaging, and e-newsletters. Through my self-education of feminism and anti-racist work (raise your hand if you grew up reading bell hooks), I connected with other like-minded activists, which included other disabled people on message boards. My mind was blown. Here were people like me – they had differences too – and they were … happy. They were in romantic relationships. They were obsessed with books and video games. And, most importantly, they called themselves disabled, without shame.

Through these new friends, I learned about the disability rights movement. I learned about people like Judy Heumann, a woman with the tenacity and unwavering advocacy I saw in my mom – and eventually myself. I learned that disability is not a bad word, and disability can mean powerful rather than pity. I was no longer confused about my identity and started to claim the descriptor of disabled.

Well, I didn’t exactly start using “disabled” – I started off with “person with a disability,” as I thought it was important that folks understood I was a person first, who happened to have a disability. It was the “correct” term used by the disability community at the time. What is great about activism, though, is it’s constantly evolving. The terms we use to describe our identities, within and beyond the disability community, change as we learn and engage with each other. Eventually, we started to question why we thought it was important to separate disability from our personhood, as though disability was something shameful or negative. I am proud to be disabled. I am also proud to be a woman, but I don’t say, “I am a person who is a woman,” so why do that with disability? And just because I was using “person with a disability,” that didn’t change whether someone automatically judged me or was ableist toward our community. Of course, these are just my thoughts – disability is not a monolith, and we should respect the terms an individual chooses for themselves.

We should also respect when a disabled person reclaims slurs to turn them into something powerful. For example, “crip” and “gimp” have been used within our community; while nondisabled folks shouldn’t use those terms in a negative light, it’s powerful when disabled people apply those words to themselves.

Almost ten years ago, I started a blog called The Geeky Gimp, where I shared tabletop and video game reviews, as well as TV and movie critiques, all under the lens of disability and accessibility. It became extremely successful, and because of it, I found freelance accessibility work for large companies like Microsoft, Xbox, Sony, and Adobe. I was also interviewed for different news outlets and other media. During the height of this work, I noticed how uncomfortable my online moniker would make nondisabled people. “Am I supposed to say this?” and “Isn’t this offensive?” were commonly asked questions when I shared my work. While I understand the sensitivity and appreciate them wanting to be respectful to the community, it was sometimes frustrating to be called out for the words I used to describe myself – as though I didn’t have a right to it. Reclaiming words that have been used against you and your specific disability is part of disability pride, and how disabled people can empower themselves when faced with hatred and segregation every day. Reclaiming words helped me shove the ableism aside as best I could – and get on with my life as best I could, alongside other disabled people and our allies.

This disability pride month, I am leaning into my disabled origin story, recognizing the reasons disabled people often struggle with their own identities – and may feel uncomfortable with labels. Internalized ableism is prevalent in our communities, and I hope we can make space for them in our disability rights movement. When media about disability is so often negative and full of stereotypes, and society is only shown these negative portrayals which can embolden ableism, it is easy to see how someone who is disabled would internalize these and feel shame for who they are. Everyone is at a different place in acceptance and understanding of disability within themselves, and we should allow them to grow without shunning them. If we come together, through advocacy and community-building, whether in-person or online, we can also educate nondisabled people alongside the work we do.

No matter where you are, I wish you a Happy Disability Pride Month.

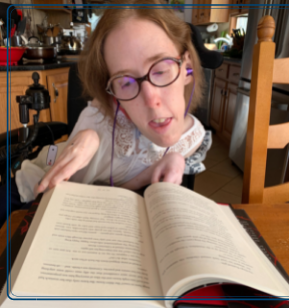

Erin Hawley is from Keyport, New Jersey, and works as the Communications and Digital Content Producer for Easterseals National. She is also a content producer for her YouTube channel From Erin’s Library, where she shares her bookish opinions, travels, and family life. Erin runs the Disability Readathon with her friend Anna, which focuses on authentic disability representation in media. She is also a gamer, and has worked with companies like Microsoft, Logitech, Adobe, and Electronic Arts to ensure accessibility and inclusivity is not an afterthought. Erin’s work has been featured in The New York Times, USA Today, HuffPost, and other publications.