ASL in Education: It’s Not Just a Trend

Editor’s Note: Allison Friedman is an educator, advocate and artist with experiences addressing common barriers that people within the Deaf community might face when it comes to education. Among the many things she does, she provides ASL access for people in the Deaf and blind community. We had a conversation about the importance of inclusion in education, including what others may not realize about Deaf culture in today’s “trendy” landscape.

Let’s talk a little bit about your background. How did you get where you are today?

Let’s talk a little bit about your background. How did you get where you are today?

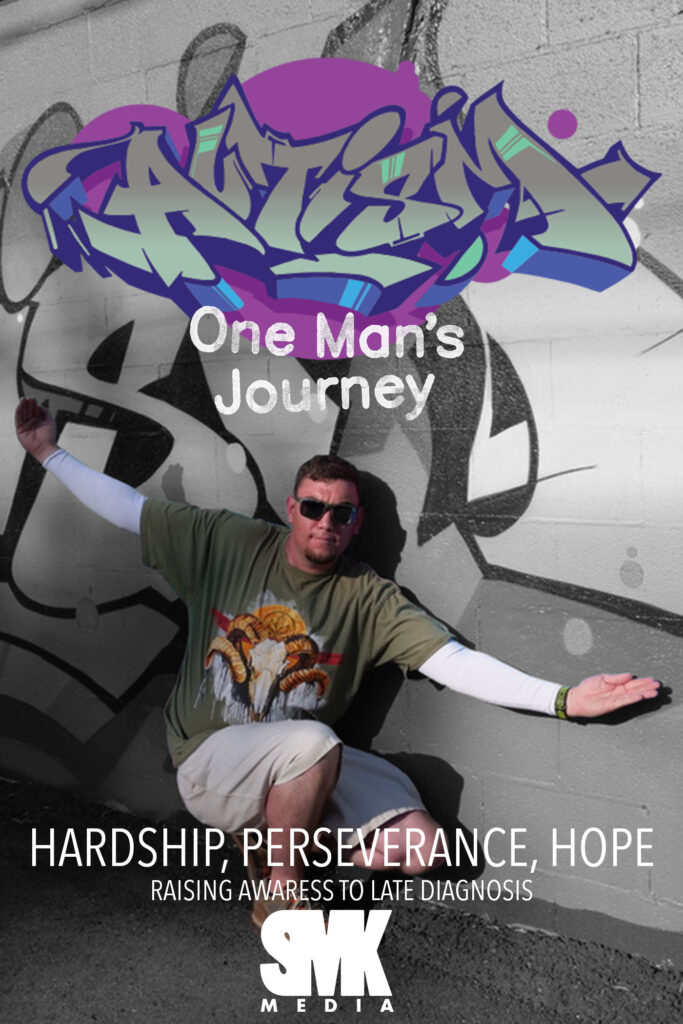

Allison Friedman: I grew up in Chicago, Illinois. I’ve always had a passion for the arts and I’m a professor and an advocate. I’m involved in several programs that are trying to spotlight different walks of life for different individuals. I’m very passionate, creative, and I work in the film industry, too. I help people get an insight into what it is like to be a person with a disability.

You have a lot on your plate, it seems.

Allison Friedman: I do! But from here, I do want to go ahead and talk about my journey as a Deaf individual and being a part of the disabled community.

What would you say is one accomplishment that stands out during your career?

Allison Friedman: Oh, that’s a tough one. I do have several, but the one that sticks out happened when I was working at Columbia College in Chicago. They invited me to do a TEDx presentation, and gave me a theme for it: essence.

Wow. That’s a pretty broad topic! What did you come up with?

Allison Friedman: My presentation focused on sign language and human connection. I am passionate about sign language and ensuring Deaf children have access to their own language. For the project, we surveyed several Deaf children who were language deprived, including my own father, who, for 13 years, didn’t have access to any of those resources for him. That really hit home for me.

I can imagine why –13 years old without any of those services?

Allison Friedman: Yes. My father, again, he didn’t have language until 13 years later. My grandparents didn’t know that there was a Deaf school.

So, your father never went to school at all?

Allison Friedman: Oh, he finally did go — as soon as my grandparents found out there was a school for the Deaf, they sent my father there and that’s where he really thrived and came into his own being. All those resources available for him there played a huge impact in his life.

How about you? What was your schooling like?

Allison Friedman: Growing up, I didn’t see ASL in the public, not until I was older. And that’s why I’m really thankful to social media and also Gallaudet University. American Sign Language wasn’t really recognized as a language until the 60s. And having it recognized as a language and also being validated as a community was really beneficial to us.

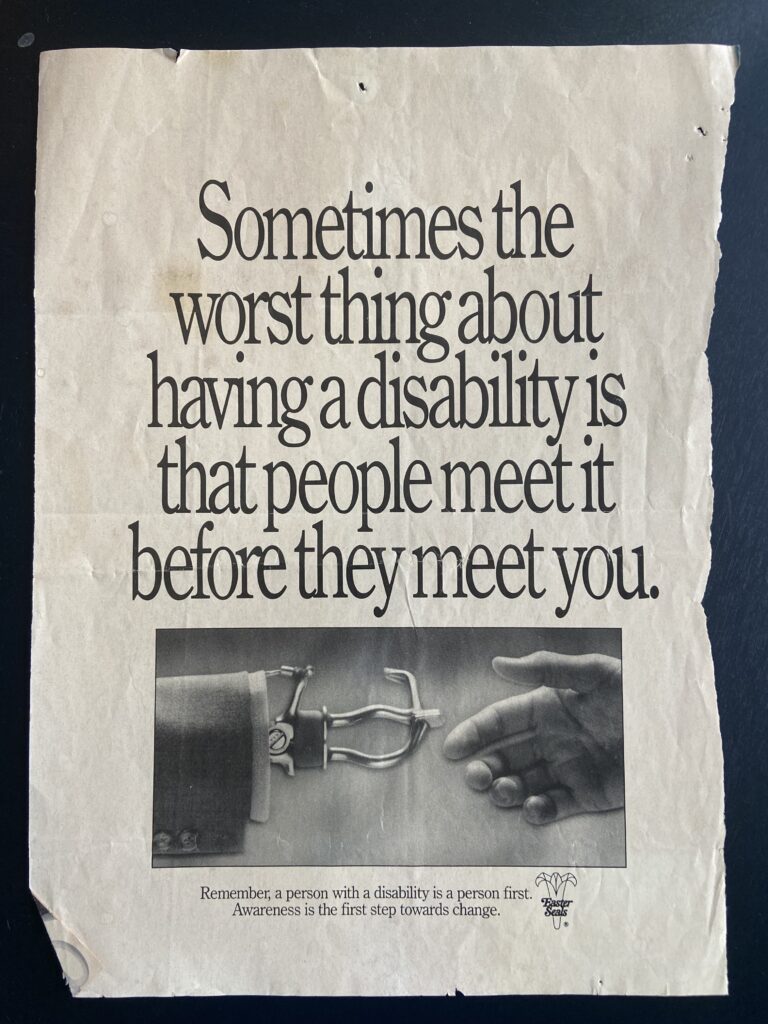

Nice! Sounds like advocating and teaching and helping people understand more about the Deaf community is paying off! What is something you wish more people understood, actually really got, about the deaf community and ASL in general?

Allison Friedman: I’m happy that ASL has gained more recognition globally, but Deaf children are the ones in crucial need of it. That’s something I want to really emphasize. Again, my father didn’t have language until 13 years. ASL is something very trendy now and something that’s seen as pretty cool. I want the world to know that ASL is not just a trend, it’s not just something to have fun with, but it’s actually some people’s main mode of communication for everyday life. I really want to emphasize that having language accessibility for children is what we need. There’s an irony in it being such a trend lately — seeing it at speeches, during the singing of the National Anthem, more out in the public in schools and colleges — while Deaf children still struggle sometimes getting access to ASL.