People with Disabilities Take the Stage Tomorrow at Chicago’s Victory Gardens Theater

by Beth Finke

Public speaking comes fairly easy to me. Acting on stage does not. But that’s exactly what I doing at Chicago’s Victory Gardens Theater, 2433 N. Lincoln Avenue t,omorrow August 13. at 2:30 p.m.

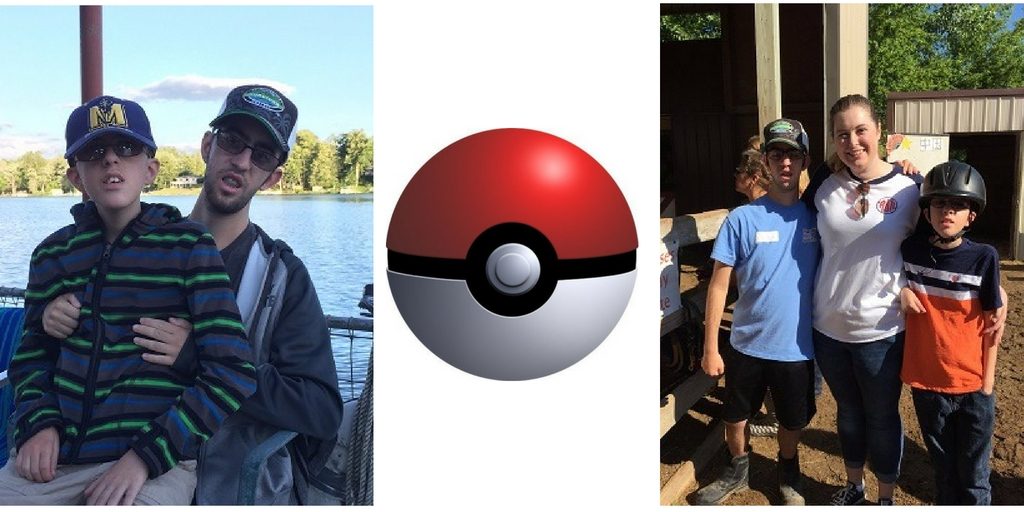

My class: (Clockwise – Andrew Lund, Beth Finke, Kathleen Guillion, Rukmini Girish, Michele Lee,, Whitney the Seeing Eye Dog, Grishma Shah) Courtesy Neo Futurists.

Some back story. Earlier this year I attended one of two accessible performances of Too Much Light put on by the Neo-Futurists. The Neo-Futurists are a collective of Chicago writers-performers “dedicated to creating honest, unpredictable theatre,” and in Too Much Light productions cast members attempt to perform a perpetually rotating list of two-minute plays in 60 minutes.

After the success of their two accessible performances this year those honest and unpredictable Neo-Futurists took things one step further. They used funds from grants they’d received from The Chicago Community Trust and Alphawood Foundation Chicago, and teamed up again with the Victory Gardens Access Project, to offer their popular “Intro to Too Much Light play writing program” in a class accessible to performers and writers with and without disabilities. The class was offered free of charge. I couldn’t resist.

The hope was that half of the participants would identify as having a disability. The Neo-Futurists achieved their goal. In fact, we outnumber the others: of the seven performers, Two use wheelchairs, I am blind, and one uses a prosthetic arm.

Over the course of ten three-hour sessions every Saturday (we started on June 4, 2016) the seven of us have:

- explored the process and tools needed to create a two-minute play

- followed the Neo-Futurist tenets of honesty, brevity, audience connection and random chance to write plays from our own life experiences

- examined specific play formulas and styles that are similar to plays performed in Too Much Light

- pitched a few of our plays to teachers to have them choose which ones would be performed tomorrow

These productions used to be called Too Much Light Makes the Baby Go Blind. I’m not sure that they took the Blind word out because I am involved, but I must say, I prefer the shortened title.

And while we’re mentioning that blindness of mine, I need to tell you that losing my sight some twenty-odd years ago left me with a unique version of paranoia. While I don’t mind people looking at or listening to me when I’m sitting or standing still (like when I’m giving a talk), the thought that people might be watching me attempt a task — even one as simple as finding a doorknob — fills me with anxiety.

I started waking up Saturdays wondering why the heck I signed up for this thing. The commute to Victory Gardens isn’t easy, days off work are precious, I stink at memorizing lines, and I hate having people watch me perform.

I liked learning about play writing, though, and every week I grew more fond of our teachers and my classmates. Most of them have acted before. It was a treat to experience their work, and hear it improve from week to week.

I stayed in class, and was determined to keep news of this tomorrow’s performance a secret from my friends. But then last Saturday we had our dress rehearsal.

That’s me in the spelling bee piece.

I have speaking parts in a play one classmate wrote about a spelling bee and in one another classmate wrote about a trip overseas. Whitney does not have a speaking part (Seeing Eye dogs are not allowed to bark). She plays a major role in a play I wrote about the internship at Easterseals Headquarters that led to the job I do here now, so her name is in the program on the cast list: she’s Whitney the Seeing Eye dog.

The four of us with disabilities wrote some plays that address accessibility, and many others that don’t mention it at all. One thing the plays have in common? They’re all pretty good.

So, I changed my mind. Everyone should come tomorrow.

The performance tomorrow won’t go any longer than 45 minutes and will feature live captioning and American Sign Language for people who are hard of hearing and audio headphones for people who want the action on stage described. Victory Gardens is wheelchair accessible, and a touch tour of the stage and props will take place ahead of the show at 2 pm for anyone interested.

The play starts at 2:30 tomorrow, so if you live anywhere near Chicago please come experience it for yourself. No need to RSVP, and no need for tickets, either: it’s free!