A New Cookbook for People with Dysphagia Features Favorite Recipes

by Beth Finke

I am pleased to introduce Colleen O’Day as a guest blogger today. Colleen is a Senior Outreach Coordinator at 2U and works with schools to create resources that support K-12 students.

by Colleen O’Day

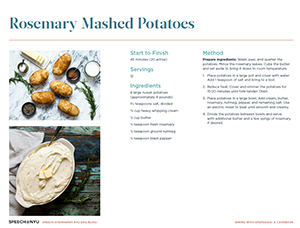

A recipe for rosemary mashed potatoes from the cookbook. Click for a larger version.

NYU Steinhardt is changing the conversation on what eating can look (and taste) like for patients with dysphagia. According to The American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, 25% of adults in the United States are impacted by dysphagia.

Food is something everyone should be able to enjoy. Knowing this, Speech@NYU, New York University’s schools online master’s in speech-language pathology created Dining with Dysphagia: A Cookbook. The cookbook is a collection of recipes that are both easy to follow and easy to swallow.

Based on the NYU Steinhardt’s annual Dysphagia Iron Chef Competition, the goal of these recipes is to make eating an enjoyable experience for individuals with all levels of dysphagia. The annual competition is the capstone project of the intersession class between NYU graduate students from the nutrition program and the communicative sciences and disorders program to learn how to manage the needs of clients with different stages of dysphagia. The students create recipes as part of case studies for real patients.

One example from the 2017 competition was a young boy with autism who would only eat white, soft foods. The NYU students had to create a visually appealing, appetizing and nutritious meal that was completely white but also easy to swallow. Other cases from the competition included clients who had more medically-focused diagnoses.

“Food is nurturing, and too often it’s assumed that when someone is sick, we should just give them calories and nutrients. That’s not what food is, and we wanted to emphasize in this intersession class that regardless of a medical condition, we should always think about the importance of food – especially when someone’s sick,” says Lisa Sasson, clinical associate professor in the Department of Nutrition, Food Studies, and Public Health at NYU Steinhardt.

You can see (and taste!) for yourself by reading and trying out recipes from the cookbook here, and if you’re interested in learning more, check out NYU’s online masters in speech pathology program.

Smart phones, yes. Smart people, not always.

Smart phones, yes. Smart people, not always.

Quick update on the disability lawsuit filed against Hamilton the Musical: A

Quick update on the disability lawsuit filed against Hamilton the Musical: A

“I would’ve made sure it was accessible if we were closer friends.”

“I would’ve made sure it was accessible if we were closer friends.”