Remote Learning and Higher Education from Home: Benefits for Students with Disabilities

by Team Easterseals

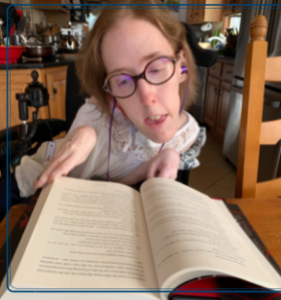

Erin Hawley, Digital Content Producer for Easterseals and the host of Disability Readathon, received her master’s degree in English from home. Although her story predates the global pandemic, her experience shows the ways that we can make technology and alternative education formats work for students with disabilities, and not against them.

Erin Hawley, Digital Content Producer for Easterseals and the host of Disability Readathon, received her master’s degree in English from home. Although her story predates the global pandemic, her experience shows the ways that we can make technology and alternative education formats work for students with disabilities, and not against them.

What did you receive your master’s degree in?

In a fully remote learning program, which was accessible to me, I received my master’s degree in English with a concentration in Multicultural and Transnational Literatures — which is one of my passions!

What helped you make the decision to pursue your master’s degree from home?

When I went to school for my bachelor’s degree in 2001, I lived on campus and drove my wheelchair to and from class every day. While I’m glad I had the campus life experience, it was logistically very difficult for me as I had to regularly navigate flooded or snow-covered walkways with my wheelchair and/or had to leave class early to attend to my medical needs.

Furthermore, I also dealt with professors who refused to accommodate me in labs (I started off as a biology major!), by not allowing my nurse to assist me with certain class activities. It was, at times, very stressful. I found myself taking fewer classes each semester to make it easier on myself, so, I graduated after 5 years with a bachelor’s degree in English.

After I graduated, I was not finding any stable jobs that aligned with my bachelor’s degree and I thought getting my master’s degree would open more opportunities. However, I knew that campus life was not a possibility for me anymore since I did not have reliable accessible transportation, and I was over the age of 21 years old resulting in me losing most of my home-care nursing hours through my medical insurance. I require 24/7 care if living by myself.

Therefore, I started looking for online programs to pursue my master’s degree in English. At first, finding the right online program that would lead to an accessible career for me was difficult. That meant, for a long time, I lived on SSI and any freelance writing gigs I could find. I did not have the financial freedom I wanted, and I hated having to ask my folks to help pay for my student loans.

I do have to say, in this regard, I am very privileged since a lot of families would not be able to offer financial support to relieve the pressure of student loan debt. Additionally, it’s important to note that a lot of people with disabilities may not be able to live with their parents for a myriad of reasons, whereas I was able to.

Thankfully, in 2012, I found a reputable University that had a fantastic program where I could pursue my master’s degree in English, fully remote. So, again, with the help of my family and more student loans (I’ve just accepted the fact I will be forever in debt) — I enrolled!

It was all worth it, because after graduating in 2016, that degree helped me land a fantastic job here at Easterseals as a Communications and Digital Content Producer, where I use my writing and researching skills daily. Additionally, my position is accessible to me, as it is fully remote!

If receiving your master’s degree from home was not an option, would you have pursued higher education in the physical classroom?

No, I wouldn’t be able to. Due to the nature of my disability, transportation to and from a campus is difficult. Additionally, I would not be able to live on campus either because I require 24/7 care, and my care hours have been cut due to my age and medical insurance limitations. In a nutshell, on-campus learning is not accessible to me. Remote learning is accessible to me and enabled me to pursue higher education.

In your opinion, how does remote learning/working help the disabled community?

My experience that led me to remote work and remote learning is common among the disabled community. Remote opportunities are vital for people like me, who cannot drive, who do not have PCAs, nurses, or a slew of other reasons that make in-person learning/work impossible. Remote options open more opportunities for education and employment to people in the disabled community.

Remote learning/working is accessible to me and made it possible for me to achieve higher education and gainful employment.

Unfortunately, accessibility, even when it’s officially regulated, is still largely at the discretion of nondisabled people. Even though I received services and supports from the disability department for my undergraduate degree, I still encountered ableist professors, and had difficulties navigating the campus.

It’s important to note, that just because it’s possible to learn/work remotely, it doesn’t always mean that it’s automatically accessible. Nothing is ever free of ableism. I urge people with disabilities to constantly advocate for their accessibility needs. This is vital. Additionally, institutions and companies, with and without remote options, must constantly evaluate their accessibility. It’s crucial that institutions and companies have open communication so when a person with a disability advocates for their own accessibility needs, they are met with support and understanding, which leads to change, which leads to accessibility, which leads to progress for all people with disabilities.

In your experience, do you think there is any difference in the quality of education — learning from home versus in the actual classroom?

I do! I found remote learning more accessible to my needs, and so I feel like the quality was better. I retained more of what I was studying because I didn’t have to worry about all these extra ableist, inaccessible things that weighed so heavily on me during my undergraduate experience.

I need to mention that people with different disabilities might not have the same positive experiences as I did with remote learning. Everyone learns differently, and everyone has different accessibility needs. However, in my experience, remote learning was beneficial to my accessibility and learning needs.

How has technology enhanced the remote learning/working experience?

Advancements in technology have made remote learning and remote working faster and more efficient for me, personally…. and so much has changed!

When I was working towards my bachelor’s degree in 2001, I didn’t own a cell phone and Zoom didn’t even exist yet. Even when was pursuing my master’s degree in 2016, Zoom wasn’t a thing.

In my master’s program, everything was done through message boards and email, which was both great for my physical disability and my anxiety. I was able to take my own notes and use PDFs instead of bulky and heavy textbooks. I was able to attend to my medical needs without missing class.

Now that we have even more advanced technology, I feel like anything is possible, as long as it’s accessible.

As noted in the Easterseals Study on the Impact of COVID-19 on People with Disabilities, many disabled people may not have access to broadband internet and technologies needed to pursue remote learning or work. It’s important we, as a society, meet those challenges for full diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility. At Easterseals, this is something we are committed to.

Any thoughts on productivity levels while remote learning/working?

Distractions at home are sometimes a struggle, which can impact productivity. I found that making lists and sticking to them daily was a huge help in my productivity. Now I probably work too hard! Which is its own problem, but I have since set a strict “no working after 6pm, unless absolutely necessary” rule that helps keep me in check. This is an aspect of self-care, which is so important.

What are your thoughts on the importance of socializing while remote learning/working?

I’m a complete introverted homebody, so I don’t mind missing out on a full classroom or office. I know that isn’t the case for a lot of people, which is why apps like Zoom are so vital to staying connected.

What is your advice on how to best prioritizing mental health while remote learning/working?

Remember to step outside or away from your desk if you need it. Set working/studying hours and stick to them. Both you and your work will be better for it.

As the world grapples with the global pandemic, remote learning/working has become the norm. In a post-pandemic future, do you think remote learning/working will be here to stay? Why or why not?

I really hope it does. So many opportunities became available for people looking for work, especially adults with disabilities. I do hope that young kids can start going back to school safely, because I know many are falling behind because they need that social interaction and one-on-one support in the classroom – but a remote option for college, or even high school students, should always be available.

What are the key takeaways society can gleam from the experience of remote learning/working?

The pandemic showed that productivity of remote work is still high, in many cases higher, because folks are more comfortable in their own homes. People don’t have to waste time and stress in traffic. Employee mental and physical well-being leads to success.

What aspects of remote learning were the easiest to adapt to? What were the most challenging?

Being able to learn at my own pace in a comfortable environment was the easiest to adapt to.

The most challenging thing to adapt to while remote learning (and working!) is my loud family who doesn’t quite understand, “shh, I’m working/studying!” Somehow their voices always carry through two closed doors. Sometimes, staying focused amidst that can be a challenge.