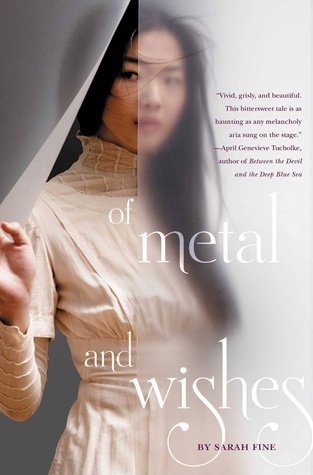

Book review on disability representation: Sarah Fine’s “Of Metal and Wishes”

by Elsa

Here’s our public relations and social media intern Allison Mulder with a new book review and how authors approach disability in their stories.

by Allison Mulder

Of Metal and Wishes, the first in a young adult duology by Sarah Fine, made me question the ways some books regard disabilities and the use of prosthetics.

In Fine’s book, a ghost wanders an industrial, harshly managed meat factory answering wishes in exchange for offerings. The ghost in Of Metal and Wishes has a lot in common with the one in Phantom of the Opera — he has the same fascinating talent, the same misunderstood innocence and the same tendencies toward obsession — but Fine’s ghost is a mechanical genius rather than a musical one.

The victim of a slaughterhouse accident, he was torn apart then repaired with mechanical limbs of his own invention. These additions function almost seamlessly—and feel familiar within the genre alongside other fantasy and sci-fi prosthetics (cyborgs, for example).

I did like this book overall, but one thing kept nagging at me: the way the heroine, Wen, regards the Ghost’s robotic prosthetics. She talks about the distinctions between the Ghost’s human half (beautiful, warm, innocent, etc.) and his mechanical half (inhuman, cold, disturbing, and so on).

Maybe this line where Wen describes Bo, the Ghost, can help illustrate my reservations best:

I see him, the parts that are whole and the parts that are shattered. He is human, he is a boy, he is evil and good fused together.

Although it’s not overt, I couldn’t shake a persistent sense that in this book, injury is equated with evil, wholeness with good. The word “ruined” kept popping up — Wen couldn’t bear to see the Ghost or other “whole” workers ending up broken forever.

These associations feel familiar. But should they? I certainly wouldn’t call injury desirable, but I don’t think it needs to be the irreparable forever flaw implied by some of the language in Of Metal and Wishes. People with injuries can live healthy, full lives. They can experience horrible things, and show amazing resilience.

A few factors complicated my reading of this book. One is the way the factory in the book throws injured workers out onto the street, so in some ways their livelihoods are literally ruined. Another is the way Wen’s feelings seem to change toward the end of the book, where she says, “There is a beauty in Bo that is not just in spite of his wounds, but because of them.” This comes mere pages after the line “If he loses his other arm, he will lose himself.” Even if this is Wen vocalizing what she thinks Bo believes, what about the lines where she thinks “about what could have been for him. All that brilliance, shredded by the harshness of the factory, warped by loneliness.” Is it just the loneliness that has caused some of Bo’s views to become twisted? Is the shredding literal, or a shredding of the spirit, or a mingling of the two?

In the end, I’m left puzzling over how much of these ideas are flawed character views that we are meant to question, and whether Fine succeeds in flipping this perspective at the end.

Ultimately, I think Of Metal and Wishes offers a lot to consider, and I’d love to hear input from you: What do you think of how disability is treated in the book? What about in other stories, like the original Phantom of the Opera, or other stories involving magical/super-high-tech prosthetics? Share in the Comment section below.