Book Review: Lisa Fenn’s “Carry On”

by Beth

Two years ago, while the Summer Paralympic Games were about to start in Rio, I heard a story on NPR about two teenagers with disabilities who ended up on the same high school wrestling team in inner city Cleveland. Dartanyon Crockett was legally blind as a result of Leber’s disease and Leroy Sutton lost both his legs at 11, when he was run over by a train. The ways these wrestlers worked together and cared for each other motivated me to write a post here about cross-disability assistance.

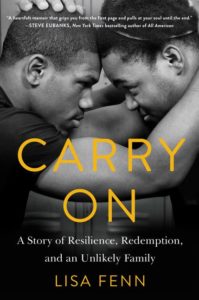

Fast forward to 2018. While gearing up to watch the 2018 Winter Paralympic Games in March, fellow blogger blindbeader remembered my 2016 post and decided to read the book an ESPN writer wrote about those two wrestlers: Carry On: A Story of Resilience, Redemption, and an Unlikely Family. I was flattered to hear that blindbeader had rememberred my post from all those months ago, then delighted when she generously agreed to let us publish an excerpt here of the thoughtful and honest book review of Carry On that she’d originally published on her Life Unscripted blog.

by blindbeader

Lisa’s Story

This story is deeply personal. While it is interwoven with strong and sharp threads of Leroy’s and Dartanyon’s stories — and those of other key figures — this is Lisa’s story. From early childhood memories to blustering and fumbling her way to a dream job to high school wrestling matches and beyond, We get to know Lisa as a warm-hearted woman who yearns for a family. And she definitely gets her wish! We’re introduced to athletes, to coaches, to parents and siblings. We laugh, we cry, and we hope and despair. But, make no mistake, this is Lisa’s story.

This story is deeply personal. While it is interwoven with strong and sharp threads of Leroy’s and Dartanyon’s stories — and those of other key figures — this is Lisa’s story. From early childhood memories to blustering and fumbling her way to a dream job to high school wrestling matches and beyond, We get to know Lisa as a warm-hearted woman who yearns for a family. And she definitely gets her wish! We’re introduced to athletes, to coaches, to parents and siblings. We laugh, we cry, and we hope and despair. But, make no mistake, this is Lisa’s story.

Sports — The Great Equalizer?

I’m not huge into wrestling, but Lisa’s writing puts the reader in school gyms, locker rooms, and world-class sports venues. You can definitely feel her respect for athletes in their own right, though there’s a strong undertone (sometimes voiced by coaches and observers and sometimes by Lisa herself) that athletes with disabilities are not talented in their own right… they’re talented “for a legless kid” (as someone referred to Leroy). The reactions to both young men — men of colour, living in poverty, and with disabilities — are almost exclusively related to their disabilities (as many of their peers are both people of colour and living in poverty). Some are astounded that they can wrestle at all and use them as “inspirations,” others don’t want to challenge them out of fear or ignorance, and still others give them the respect of laying it all on the mat. And yet, it’s clear that wrestling — and Lisa and ESPN’s exposure — gave both Leroy and Dartanyon opportunities they otherwise wouldn’t have had.

Disability as Inspiration or Tragedy

As much as I enjoyed this compelling read overall, I had a hard time escaping the prevailing theme that disability was something to be pitied or inspirationalized. In Lisa’s career as a sports editor, she interviewed athletes from all walks of life, including a hockey player who — years before the interview — became injured and paralyzed just seconds after stepping onto the ice during his first major game (you could almost hear the sad cellos playing in the background).

Leroy and Dartanyon’s wrestling coach contacted the local newspaper to write a story about his two disabled wrestlers (clearly without consulting them); Lisa was unable to explain why she thought it was a story that needed national attention, but to her it was, so she dropped everything to fly back to her home city and interview these kids. When the resulting ESPN story aired, the resulting letters and responses left this reader with the distinct feeling that Leroy and Dartanyon were meant to be viewed as recipients of generosity and catalysts for people to look outside themselves, rather than talented athletes in their own rights.

And Yet…

No one can ignore the confluence of race, poverty, and disability, and how Leroy and Dartanyon’s families — neither of which were what many would consider “stable” — shaped their high school and college/university experiences. Dartanyon, in particular, frequently refused to be “pitied” as a blind guy, even though he could’ve made use of adapted services, because he didn’t want anyone to treat him differently. Leroy didn’t have the luxury of being able to blend in, but it is clear that his school and training environments are not well-equipped for many students (lack of uniforms and sports equipment) and definitely not set up with wheelchair-accessible buses or classrooms.

It’s hard to look away from the reality that many cards are stacked against these young men’s lives and journeys. Lisa is tireless in her desire to provide for Leroy and Dartanyon, even as her adopted and biological family with her husband keeps growing. It’s heartwarming and frustrating and an important conversation — nature and nurture and empathy and personal responsibility. It made this reader uncomfortable, and maybe that’s a good thing.

Conclusion

This book is part memoir, part sports journey, part family history. There are some deeply uncomfortable mentions of ableism, racism, and inspiration porn (based on the depiction of the ESPN piece, “Carry On”, this reader has no desire to see it). And yet, this autobiography is compulsively readable, uplifting in places, and thought-provoking. It’s definitely worth the read.